Your two main levers of profit are to lower your expenses and to raise your revenue. (Profound opening, I know. Stay with me.)

Of course, like any business owner, you should understand your costs, and you should have a sense of how those costs compare to other firms like yours, without being a slave to any benchmarks or averages. (The good and bad of benchmarks is a topic for another day.)

But the other lever—revenue—is the easier one to pull, the one that has the outsized impact on profit. And one of the easiest ways to impact revenue is to raise your prices. Not all your clients will accept a price increase of course, so earning more through improved pricing is often more nuanced than a straight price increase across all clients and services, but it’s still relatively easy to do and the impact on the top and bottom line can be significant. Let me show you just how significant by taking a hypothetical firm that is reflective of some industry averages and typical pricing success stories.

To make sure we’re isolating pricing success from sales success, let’s use the same closing ratio across multiple scenarios.

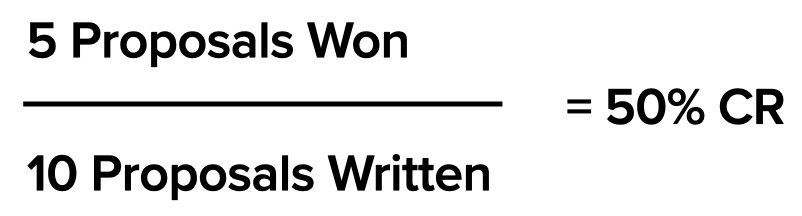

Your Closing Ratio

Your closing ratio (CR) is the number of proposals won over the total number of proposals submitted. For example, a firm that wins five of ten proposals has a closing ratio of 50%.*

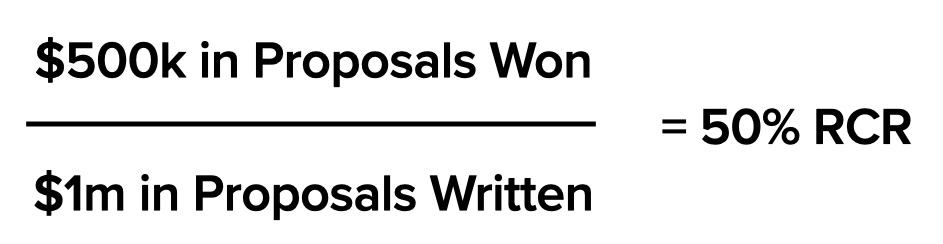

Your Revenue Closing Ratio

A more revealing ratio is what I call your revenue closing ratio (RCR). To calculate your RCR simply use the monetary value of the proposals in the same calculation. If the ten proposals written in our example are all of the same value—let’s use $100k—then the RCR is the same 50% as the closing ratio.

Still pretty straightforward. But things get interesting when you embrace multi-option proposals that I outline in Pricing Creativity: A Guide to Profit Beyond The Billable Hour.

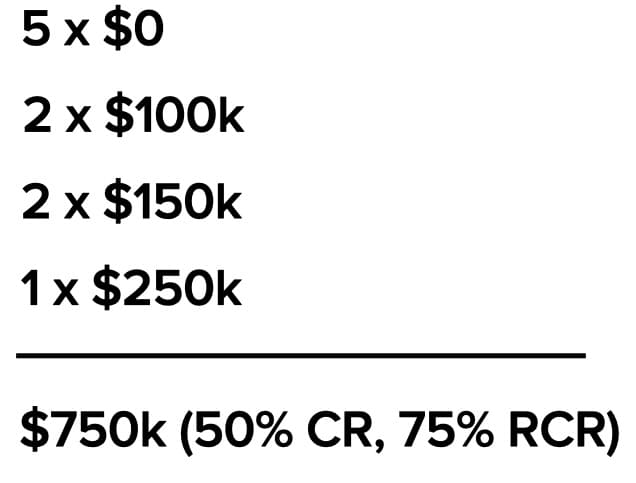

Let’s assume that for each of the ten proposals submitted the client’s stated budget was $100k, but the proposals submitted had options to engage the firm at $100k, $150k and $250k. (Note that the RCR denominator is always the client’s stated budget or the lowest priced option, which are typically the same.** RCRs start outpacing CRs when clients commit to spending above their stated budget.)

In this new scenario the 50% closing ratio doesn’t change, but in three of those five wins the firm nudges the client above their stated budget. The results break down like this:

The firm’s selling skills haven’t improved, per se—they still have a 50% closing ratio—and the clients’ budgets haven’t changed ($1m combined) but a small improvement in pricing skills and simply giving the client options has improved RCR and revenue by 50%.

Closing ratios can never exceed 100%, but revenue closing ratios can, and do. That means that some firms writing proposals for $1m in combined client budgets are closing $1m in business—and more—at close to standard closing ratios. While our example firm is only halfway there, they’re just getting started.

Upward Momentum

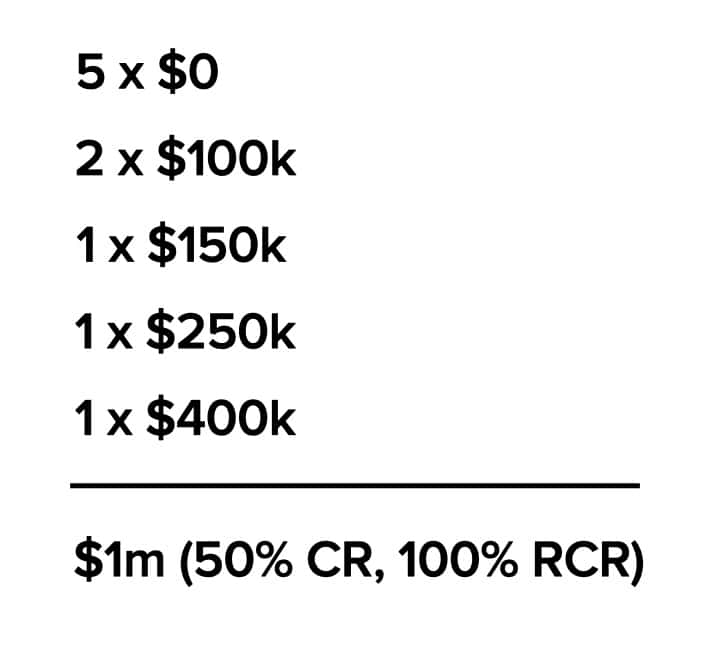

The more our firm builds pricing skills and experiments with multi-option proposals, the better their results get. With the same 50% closing ratio, they keep finding ways to expand their clients’ budgets by providing more elaborate and expensive ways to create more value (or certainty of value) all while still allowing those clients to buy at their initially stated $100k budgets, if they prefer. Where the firm once saw the client’s stated budget as a rule of law, they now feel free to present options that are limited not by arbitrary budgets but by return on value created. This sometimes leads to options that are priced at many multiples of the client’s stated budget.

And their average selected price keeps going up, with the results of their next 10 proposals looking like this:

This firm has now fully closed its revenue gap. The $500k in proposals that they didn’t win is offset by $500k in revenue that they closed above their clients’ stated budgets. (I previously wrote about how you should track and gamify this revenue above budget, or RAB.)

This 100% RCR is a threshold of pricing success that is within reach of most creative firms and one every firm should aim for. And there are levels beyond this.

The Elephant in the Pricing Room

Some will find the proposal amounts I’ve used so far to be incredulous. After all, $250k and $400k are multiples of the client’s $100k budget. Some won’t believe that a client with X budgeted would spend 4X. And others are thinking that only sinister manipulation can get a client to spend multiples of what they intended to spend.

But have you ever been hired by a client to do A, only to find out deep into the engagement that they didn’t need A at all, that what they really needed was B?

Or have you ever worked on an underfunded project where it was so clear that if the client had invested more the returns would have been massive instead of paltry?

Or have you had a client try to frame a potentially transformational strategic opportunity as a tactical project that they needed to get done quickly and cheaply?

I have found myself in each of these scenarios multiple times. On some occasions I summoned the courage to do the right thing and challenge the client to think differently or bigger. And on too many occasions I took a pass and let the client get away with a mistake or miss an opportunity.

With a multi-option proposal you can challenge the client to think bigger (in one or two options) and still allow them to buy what they intended, or spend what they budgeted—if that really is their preference—after you’ve had the adult conversation.**

You don’t raise your prices by conning your clients, you raise your prices by raising your clients.

Closing Ratios Will Go Up

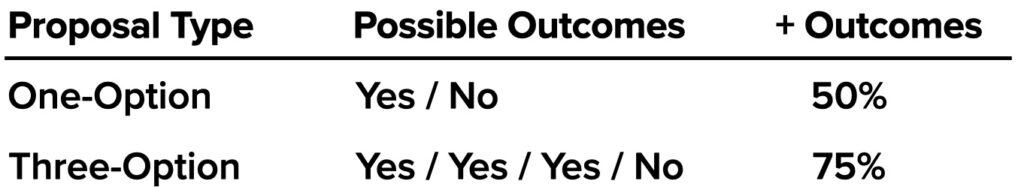

So far the closing ratio has remained constant at 50%, but the introduction of multi-option proposals almost always drives an increase in closing ratios, for the simple reason that by offering the client three options you raise the percentage of positive outcomes by 50%.

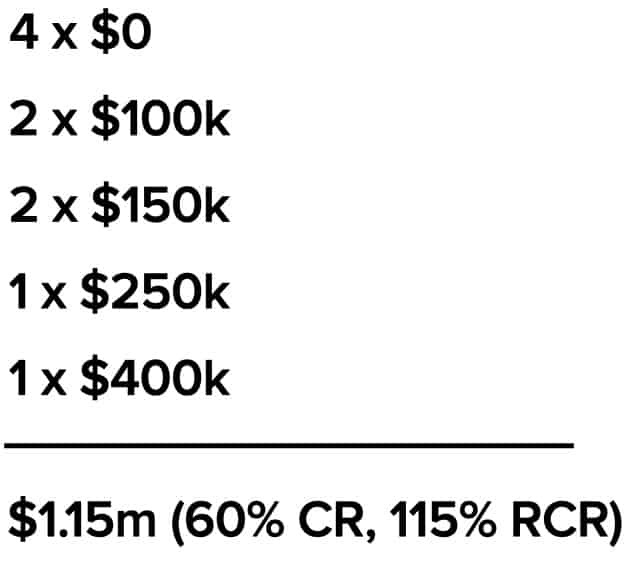

The three-option approach raises this firm’s closing ratio by another 10%, meaning one of the five loser proposals now gets accepted, driving the closing ratio to 60% (six out of ten). And let’s say that the relatively inexpensive option of $150k is selected. Our results now looks like this:

…And Up

We’re tracking a hypothetical firm, using industry averages and typical pricing success stories. Their baseline ten proposals yielded a 50% closing ratio and a 50% revenue closing ratio, generating $500k in revenue.

After introducing multi-option pricing, ten subsequent proposals enjoyed the same 50% closing ratio but their revenue rose by $250k to $750k, for a RCR of 75%.

In their next ten proposals, again with the same closing ratio, they closed their revenue gap completely, earning $1m on $1m in proposal value. That’s a 100% RCR at the same 50% closing ratio.

We then recalculated those last numbers based on the reality that multi-option proposals almost always increase closing ratios. One proposal moved from the loss column to the win column. Revenue is now up 130% (from $500k to $1.15m) with a RCR of 115%.

Gains in Qualifying

More time passes and skills keep improving. The firm is feeling confident. But their 40% loss ratio is starting to nag at them. They do a rudimentary analysis and learn that in half of those lost proposals the signs were pretty clear that they were never going to win. They couldn’t corral key decision makers, the process was driven by procurement, they could never escape the feeling of being treated like a vendor or some other factor made it obvious that two out of ten proposals never should have been written.

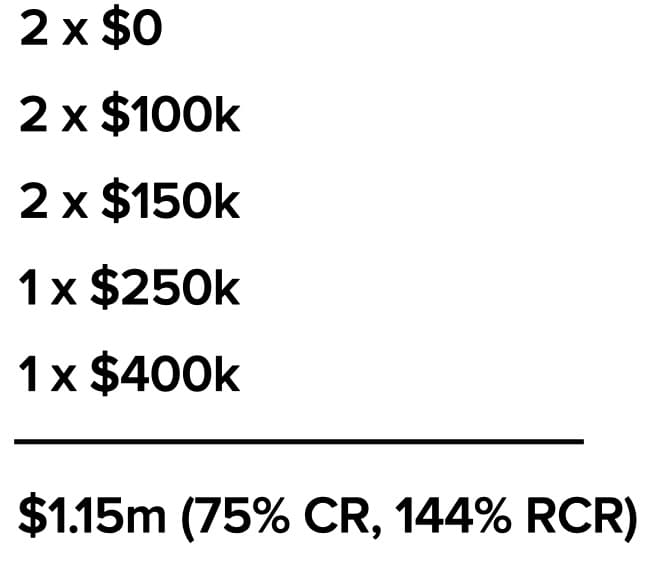

Seeing the patterns, they summon the resolve and quit writing proposals for the two out of ten proposals where it’s obvious they won’t win. This increases their closing ratio to 75% (six winners out of every eight proposals written), and it lowers their average cost of sale by 20%.

Their numbers now look like this:

Again, this example is hypothetical based on industry averages and patterns we see in our clients, but it’s not an outlier. We routinely see firms hit 100% RCRs and beyond with continuous improvement for years when they layer in better qualifying, as this firm has done, improved closing skills, more advanced pricing techniques, and perhaps changes in service offerings, target market or business model. In the typical creative firm, revenue and profit can both rise dramatically with the same expense ratio and lead flow.

It’s Pricing. It’s Always Been Pricing.

So, yes, you should keep an eye on your expenses, and yes, more leads is a better state than fewer, but neither of those levers are as easy to pull or as impactful as simply getting better at pricing. There is no lower hanging fruit on the profit tree than pricing.

It’s pricing, it’s pricing, it’s always been pricing.

Buy the book or reach out if you need help, but would you please go get that money? It’s just hanging there, waiting to be picked.

-Blair

*Multiple sources suggest that the average closing ratio for all proposals written in an independent creative firm is somewhere between 25% and 30% but it’s a curve with a fat tail.

**When you submit a proposal to a client with a stated budget, I believe you are obligated to show what you can do (profitably!) for that budget, if only to show what little can be accomplished when a project is underfunded.