Selling and negotiating are related, but they’re different enough from each other that they may require different ethical standards. (If I were in your shoes I would probably quit reading after that, or any sentence that told me to lower my ethical standards, but please hear me out.)

I have a strongly-held view of how the selling of expertise should be done. Because the sale is the sample of the engagement to follow, and the roles that each party will play in the engagement are determined in the sale, the selling of expertise should always be ethically and dynamically consistent with what it means to be an expert advisor or practitioner.

In any expert engagement the ethical standards should be high, with a premium placed on personal integrity and the preservation of a mutually respectful relationship. The dynamics should see the expert’s expertise recognized and valued, with them allowed to lead the engagement in the way they judge is best, rather than relegated to vendor status with the terms of the engagement imposed on them.

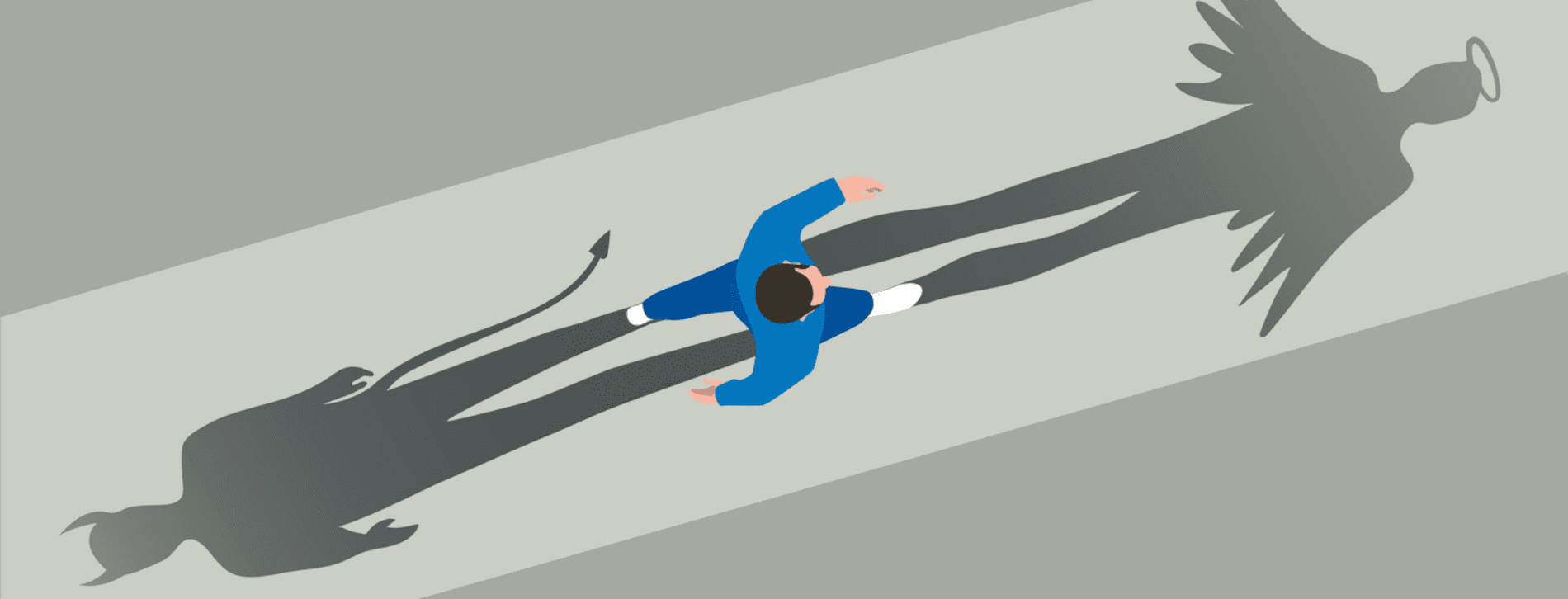

If you were to transpose this approach—let’s call it the Win Without Pitching theory of selling—into one of the schools of bargaining ethics, as defined by Wharton professor and Bargaining for Advantage author G. Richard Shell, it would land squarely in the “Idealist” school.

The Three Schools of Bargaining Ethics

Those in the Idealist school, according to Shell, view negotiations as serious, consequential acts that have no exemptions from the rules and conventions that govern a fair and just society. Idealists believe that truth, honesty and transparency are paramount. They always play the long game, ensuring to preserve their own standing and the relationship between parties. They tend to strive for win-win outcomes.

Opposite the Idealist school is the Poker school, the adherents of which see negotiating as a game in which all tactics are allowed, as long as they are legal and fiduciarily responsible. Deception and even outright lies are on the table, as are all the minigames of table thumping, chicken, good cop-bad cop, nibbling, salami slicing and more. Poker players don’t see this type of negotiating behavior as reflective of a person’s ill character—it’s a game after all*—and they don’t concern themselves too much with the relationship. Poker players play to win in a match where there can only be one winner and one loser.

The Pragmatist School lies between the Idealist and Poker schools. It’s a more flexible approach that sees the negotiator adjusting their ethics to the context of the negotiation and the ethics and behavior of their opponent. Pragmatists would prefer not to deceive but believe it’s appropriate to mirror back what they’re getting from the other side of the table, while still valuing personal integrity and the larger relationship.

Do the Ethics of Selling Expertise Apply to Negotiating?

If you subscribe to the Win Without Pitching theory of selling that I articulated at the top—an approach that largely aligns with the Idealist school of bargaining ethics—it does not follow that you should bring that ethical standard to negotiating.

Bad behavior from a buyer is an indicator that you probably shouldn’t be doing business together. I’m firmly in the Idealist camp when it comes to selling because I fail to see how adjusting your ethics to match a client’s lower ethical standard leads to a positive and mutually rewarding relationship. If a client is going to lie, withhold information, or otherwise treat you poorly in the sale, you can take that as a sign of either their poor character or your low standing in their eyes. Either is cause to walk away. Bad behavior in the sale doesn’t mysteriously get better in the engagement once money has changed hands.

After two parties have determined that it does make sense to do business together, however, the negotiations that follow are often with another party. The goals of that party—whether they’re from finance, procurement or legal—are never fully aligned with those of your client in marketing, communications or product. Your client’s goals of value creation are more closely aligned with yours than they are with those of any of the aforementioned departments. And while, if you do work together, you might have somewhat of a “relationship” with people in those other departments, it is nowhere near as deep or as vital as the relationship you must have with your direct client. Preserve the latter relationship, but if others in the client organization are playing poker, then you should play poker too, and strive for win-lose.

That is not an easy mental shift for someone who has thus far navigated the sale as an idealist. You can get caught out emotionally.

Emotional Shift Ahead

Personally, I consider myself to be in the John Wick school of negotiating. I’m an idealist until someone kills my dog. Then I murder everyone and blow up the building even if I happen to be standing in the middle of it. (If I wrote a book on negotiating it might be called “Getting to Lose-Lose.” )

It’s fun to write that cheeky statement but in reality it means I have to work hard to subdue an emotional response to a provocation from a poker-playing opponent who knows exactly what they’re doing. A mentor of mine used to say about such conversations, “It’s just data. Don’t take it personally.” You can’t be a good negotiator if you don’t create some distance between the provocative stimulus and your own emotional response. “Let me think about it and get back to you,” might be the best friend of an idealist negotiator or someone with too much skin in the game. It buys the cooling off time necessary to think more rationally about the information contained in the emotional wrapper, and to shift from idealist mode to poker player.

An Adaptive Approach to Negotiating

While I strongly believe that there is one right ethical standard for selling expertise, it’s universally understood that the best negotiating style is adaptive, in the Pragmatist school sense, changing to match the ethics and techniques of the opponent. USC Professor of Management Paul Adler coined the term “protean negotiating” to describe such an approach, named after the shapeshifter Greek god Proteus.

So while you might be an idealist who subscribes to the highest ideals of a fair and just society, and you might bring those values to bear in how you sell, you need to be prepared to shift shapes when faced with opponents who play by different rules. If the client’s negotiator is playing a win-lose game, then play the same game, be ruthless and go get everything you can. They deserve nothing less from you.

-Blair

*Like negotiators from the Poker school, I am on record as saying that selling, too, is a game. I don’t mean to imply however that the game has a special set of rules outside of societal norms. I simply mean that if you’re not having fun, you’re doing it wrong.