“All models are wrong but some are useful.”

-Prof. George P. Box, Statistician and Author

A conceptual model is a way of making sense of the world. It is a mental framework for organizing and understanding what we experience.

Many of us have a plethora of such already defined “mental models” that we use in daily life, like the Pareto Principle (the idea that a small minority of actions or players drive a large majority of results–often referred to as the 80/20 Rule) or Occam’s Razor (the idea that simpler explanations are generally better than more complex ones) or Hanlon’s Razor (the idea that we should never attribute to malice what can be explained by ignorance) or, one of my favorites, the Third Way (the idea most decisions that appear binary are not, and we should look for solutions other than the two options on offer).

Mental models, metaphors, philosophies, scientific theories and laws—to me—all fall into this broader category of “models” that are the mental frameworks we use to make sense of what we are experiencing and therefore what we might do.

Your Business Needs Multiple Models

If you run any business of expertise you will come to rely on all sorts of models. The longer you are in business, the larger your model toolbox becomes.

It’s important to be able to draw from multiple models because single-model people or businesses are like the proverbial man with a hammer viewing every problem as a nail.

It’s been proven that when making predictions (think elections or stock markets), people working from one conceptual model, on average, perform worse than chance, but the addition of a second model usually beats chance and additional models after that continue to improve performance. More models, more better.

Over 20 years ago it was explained to me that “buying is changing.” Selling, therefore, is change management. Any of the valid change management models are then easily ported over to the world of sales.

This has been immensely helpful for me to not only better understand selling but to better teach it. Importing models from other fields of inquiry or endeavor in this way can be helpful to us to understand what we experience, and also to impart what we know.

Some models, like the Trans-Theoretical Model of Change, are complex, and some models are simple and yet still profound. Robert Cialdini’s research on reciprocity is easily summarized (plant the seed for reciprocity early, when you are doing something for the other party, not afterward), yet it strikes me as a powerful model for thinking about referrals.

I think most books on leadership serve as good models for selling. For years I have used the relationship you have with your doctor as a helpful model for you to think of your relationships with your clients, across four phases of diagnose, prescribe, apply and reapply.

These are some of the models that are useful to me, but they may not be to you. A lot of people reference dating as a model for selling. While I see the parallels, I don’t find that model particularly illuminating or useful to me. We use the models that serve us. As Professor Box noted in his statement at the top, the value of a model is in its usefulness and not its veracity.

I recently spoke to a consultant who spends his mornings farming and his afternoons advising CEOs and heads of state. He explained to me how he applies lessons learned from working with animals to his consulting practice. (Among other gems, the idea that because animals cannot speak, you must spend time with them observing, without rushing to judgment.) Farming is a useful model for him. For those of us who do not farm, it’s not likely to be useful.

Models Are Approximations

Rene Girad’s philosophy of Mimetic Desire (the idea we are born desiring nothing other than the basics of life and that all other desires are learned by observing what others desire) is de rigueur right now, made popular by Girard’s famous student Peter Thiel.

In our house we have two cats, who are brothers. One brother, Max, is a living example of mimetic desire: he appears to only want what his brother Steve wants. Max is the feline embodiment of this philosophy—proof that it is a correct model of decision making. But Steve shatters this idea of the model being universally true (at least in cats). He does not appear to give a shit about what any other living creature wants. Steve is his own man, as it were.

And still I find this model useful in daily life, especially in family dynamics and my own decision making. Do I really want that? Why do I want that? Is it because someone else has or wants that? Are these really my goals? What is it that I really want?

As one tool in my toolbox, mimetic desire is useful to me. If it were the only one I used it would get me into trouble, at least with cats. Some, including Girard and Thiel, might argue that mimetic desire is “correct” as a theory and others I’m sure would take the opposite position, with each citing research in support.

As someone looking for one more model in my repertoire, however, I’m not interested in this debate. It is a model that is occasionally useful to me.

Proprietary Models Are Outcomes of Continuous Learning

While we at Win Without Pitching continue to borrow from numerous models, I wanted one overarching model that was ours. As the knowledge we gained and the curriculum we developed grew, it became obvious we needed a simple framework to contain and communicate everything.

I’m not sure I can articulate why this seems so vitally important to me but I have long intuited that the greater the complexity in a business or business challenge the greater the power of a simple model into which one can glimpse well-organized complexity.

Good models say, “This thing that you see as complicated is actually quite simple.” Bad models say, “This thing that you see as simple is actually quite complicated.”

I’ve joked for close to two decades that many creative firms share the same “bad” proprietary model. It’s usually four steps, each step begins with the same letter and that letter is usually “D.” These models are simple but tend to lack any profound insight that can only be gleaned from a depth of experience.

When you peer into them you do not see well-organized complexity, you see simple ideas simply organized (and sometimes made to look more complex than they really are.) The observer garners no new information; there is no surprise.

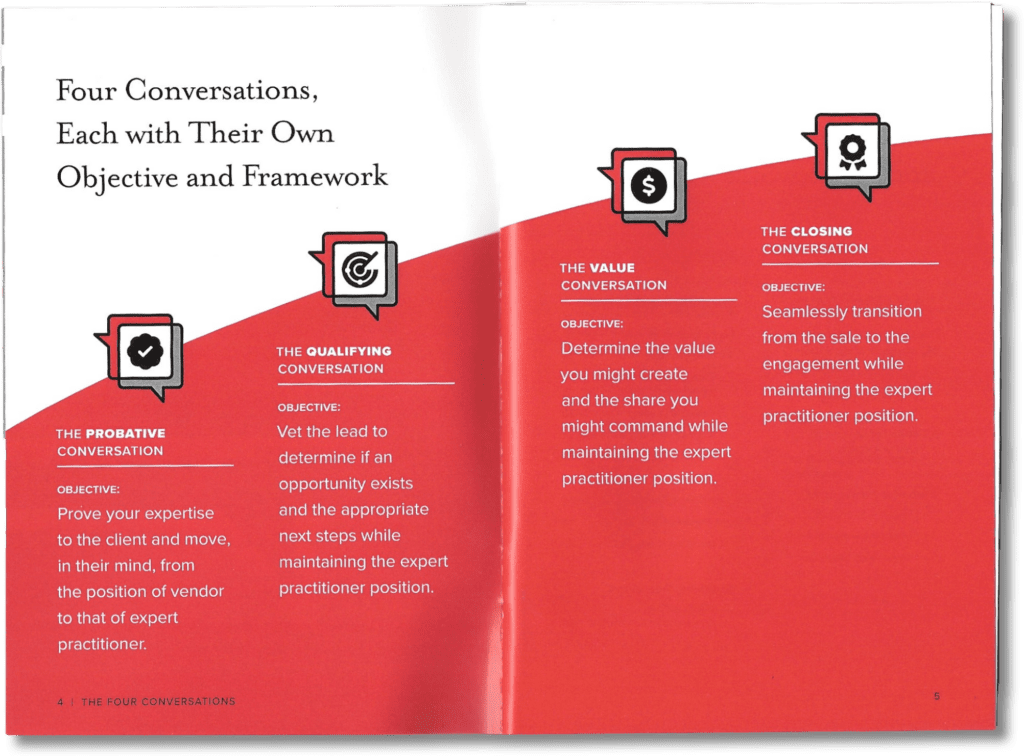

At some point I started to see the sale as a series of four linear and discrete conversations. We defined the objective for each conversation and then aligned all of our tools and beliefs to help our clients navigate to those objectives.

Today, everything we teach at Win Without Pitching is framed by this Four Conversations™ model. Our model isn’t “right” (there aren’t always four conversations, they don’t always follow the correct order, they are not necessarily discretely defined—often blending into each other; and four conversations is by no means the only way to represent the arc of the sale and the role of the salesperson) but we have found it a useful way to organize and communicate our philosophy and approach.

Prior to developing the Four Conversations model I spent years building another proprietary model. Without boring you with the details, the model lacked the elegance to be useful.

When we discovered one of our ideas or a new piece of curriculum did not fit into the model, I would expand the model to accommodate it, until the team started referring to my visual representation of the model as “the muskrat.” [Note: you should be able to draw most models in simple diagrams.]

What began as something that could be communicated via a few words and a simple visual eventually morphed into an incoherent rambling and an indecipherable diagram representing a Frankensteinian rodent.

The Four Conversations, on the other hand, is simple. New learning and training curriculum fits easily into the existing model without adding complexity. (Thank you, William of Ockham, of Occam’s Razor fame.)

If you took our Four Conversations model away from us, we wouldn’t implode or be left helpless because the model is not our knowledge, it is the framework within which we choose to organize and communicate that knowledge.

If we were stripped of the model we would simply find a new one and little knowledge would be lost. If a competitor chose to “steal” our model they would have little more than an empty vessel that they would then have to fill. That fill—the knowledge gained through experience—is the hard part.

By comparison, arriving at a model is easy, but that does not mean it is not valuable. Models are immensely valuable, and perhaps nowhere more so than in a sale.

Models Can Be Invaluable Sales Tools

To recap, models help us gain, organize and communicate knowledge. This last part of simply and sometimes profoundly communicating what we know is what makes models so valuable in a sale. They allow us to communicate a complex depth of knowledge, in a simple way, organized around a point of view.

This interplay between simplicity and complexity is vital. Our model says, “Look there’s a lot of complexity here, but we’ve been through it all and we’ve organized everything into an easy-to-understand framework that makes it all quite simple.”

Struck by the simplicity, the client peers in to see the well-organized complexity and thinks, “These people know what they are doing. We are in good hands.”